Ali Phi’s Liminal Exhibition Unveils the Unseen at 212 Photography Istanbul

- Onur Çoban

- Sep 4, 2025

- 5 min read

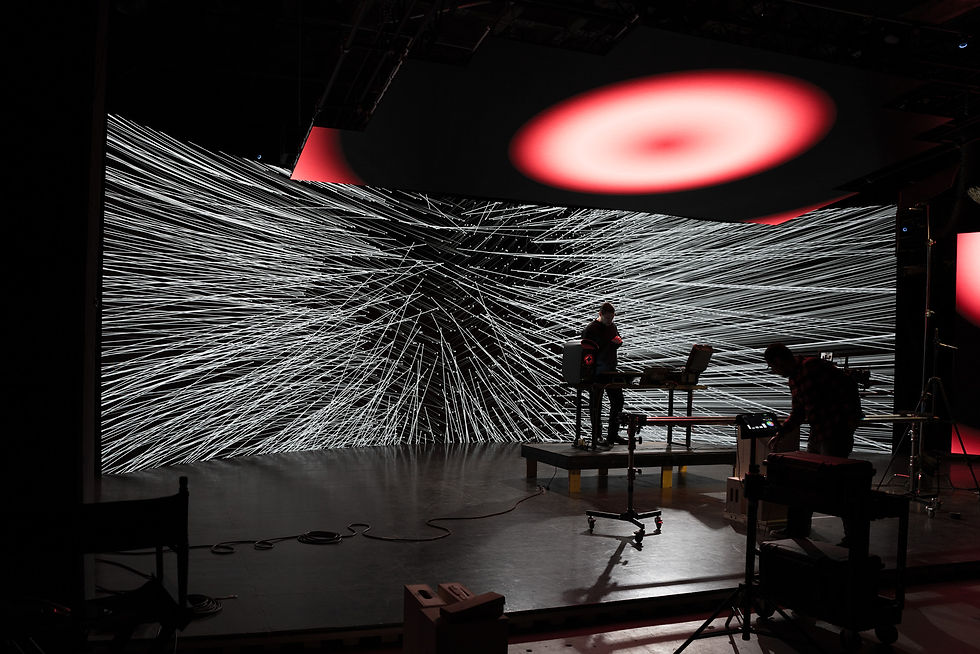

Decompositions for Computers ©Ali Phi

Taking place from September 27 to October 12, the eighth edition of 212 Photography Istanbul is set to offer the city an exciting route through a program of photography and creative disciplines. Spread across nearly 30 venues on both sides of the city, the festival stands out with long-running exhibitions and a wide range of events. Once again this year, 212 Photography Istanbul aims to reveal both the historical and experimental layers of photography through its multidisciplinary program.

This year’s program features artists from various disciplines, among them transmedia artist Ali Phi, who brings together art, science, and technology. His exhibition Liminal explores the transitional spaces between the physical and the digital through light, interaction, and the unveiling of the unseen. With his interactive installation, Phi proposes an experience that draws on data-driven works shaped by architectural echoes, fleeting patterns, and algorithmic traces. Inviting the audience to engage both perceptually and conceptually, the exhibition focuses on the aesthetic and intellectual potential of the digital age, shaped by Phi with poetic sensitivity. We spoke with him about his work featured in the festival and his creative process.

In Liminal, which will be presented as part of the 212 Photography Istanbul Festival, the main themes are the revelation of the unseen and the transitions between the physical and the digital. How do you define these concepts within your own practice, and how does the exhibition embody this definition?

In my practice, the unseen refers to layers of reality beyond immediate perception—data flows, shadows, reflections, and digital traces that rarely surface to our senses. The transition between the physical and digital happens when those layers are translated into felt experience through light, sound, and interaction. Liminal embodies this by turning the gallery into a responsive threshold where presence has agency: viewers’ movements and shadows modulate particle systems, projections, and generative sound so that the intangible becomes tangible.

The visual language on the transparent screens extends from my recent generative audiovisual project Decompositions for Computers, a multi-year inquiry into “digital waste”—the ecological and cultural residue of our online lives. That work maps techno-social activity and case studies of personal and corporate data stewardship to reveal the hidden costs of storage and circulation (including the carbon intensity of cloud infrastructures), reframing our everyday clicks and uploads as material with environmental weight. It unfolds across decades of internet growth—drawing on sources like World Bank adoption data and industry reports—moving from early web communities to the rise of non-human traffic, and into speculative territories such as the future “dead-to-alive” ratio of social media profiles. These data narratives drive generative systems—AI-assisted portraits, evolving fields, and audiovisual structures—that Liminal recontextualizes in space: the code “listens” to bodies and architecture, so audience gestures fold into this cartography of digital detritus and make its otherwise invisible dynamics perceptible in real time.

Decompositions for Computers ©Ali Phi

How do audience movement, live data, or sensor inputs trigger the viewer’s experience? Which audience behaviors lead to which visual/auditory transformations?

In this presentation of Liminal, the work does not run live, sensor-driven code; instead, the projected imagery comes from my real-time generative systems and carries the same logic. The interaction is spatial and embodied: the audience shapes the piece by moving the transparent screens, choosing their vantage point, and navigating the space they assemble. You’re not pressing buttons—you’re composing the image with your body and the architecture.

Deliberately, I’ve removed sensorized interactivity—no computer-vision tracking, obstacle-detection logic, depth cameras, or “instrumented” sensing. Agency shifts from coded triggers to physical decision-making. That’s why the installation uses raw wood and metal: material honesty encourages direct handling, makes the mechanics visible, and resists preciousness. It underlines that interaction here is analog and spatial, not mediated by hidden digital thresholds.

Likewise, I work against precise video-mapping. Rather than edge-matched projection, the image is larger than the screens by design—there’s intentional “light spill.” Viewers effectively crop the light, This approach extends a throughline in my practice: I build reflection machines or false mirrors—systems that confront viewers with themselves, each time flavored by different “spices” of visuals, space, and sound. In earlier sensor-based works (such as Lima and other installations), gestures modulated parameters directly—proximity increased density/velocity, clusters raised complexity, stillness drifted the system toward minimal states. Here, even without live sensors, the concept of viewer agency remains: with every group, the layout reconfigures, and each round of presentation yields a different cut of light, a different geometry of seeing.

2024, Zall Gallery, Tronto, Ontario, Canada, Photo by Sardar Farrokhi

How do you conceptualize the “architectural echo” in the experience you propose? Could you talk about the relationship between the physical qualities of the space and the code/algorithm?

For me, “architectural echo” is the way a space answers back when you introduce light, sound, and bodies into it. It’s both literal—secondary reflections, occlusions, reverberation—and conceptual: the building becomes a co-author that shapes what the audience perceives. In my performances, I actively treat the space and its architecture as the canvas. Past presentations in historic buildings, post-industrial warehouses, and urban sites have all proven that the room’s height, texture, circulation, and reflectivity aren’t just constraints—they’re pigments. Stone softens and diffuses; glass doubles; concrete cools; metal throws sharp highlights. I design the algorithm like a score with open parameters, and the site supplies the boundary conditions that make each presentation unique.

So, the algorithm proposes a grammar; the architecture and the audience conjugate it. That’s the echo: the building’s physical qualities—height, texture, reflectivity, circulation paths—return the work to us transformed, and the piece embraces those returns as part of its composition.

Portrait ©Ali Phi

How do your decision-making stages work in the creative process: which software/tools or production methods do you use, and how do they determine certain aspects of the experience in the exhibition?

I begin with sketches, research notes, and a map of behaviors—what should accumulate, decay, or break symmetry. From there I prototype in TouchDesigner (with GLSL where needed), use Python for tooling and parameter sweeps, and shape sound in Ableton/Max for Live. These tools let me define families of behaviors—tempo, density, contrast, thresholds—rather than fixed scenes, so the experience can stay responsive to context.

My references come from Middle Eastern geometry and the greater Iranian plateau—repetition with variation, layered translucency, and measured asymmetry. That lineage, including its mystical attention to presence, guides how I use Western technologies: not for spectacle, but to focus perception. Production decisions follow the prototypes—projector optics, scale, material transmissivity—and I iterate quickly: simulate, test in a small rig, adjust, and document. The final work is a score with open parameters: tightly authored in its logic, flexible in how it’s lived.

2024, Zall Gallery, Tronto, Ontario, Canada, Photo by Sardar Farrokhi

What are your plans after Liminal? Do you plan to explore new formats, collaborations, or different spatial experiences with this practice?

After Liminal, I’m continuing to develop Decompositions for Computers across formats—both as a performance and as installations that adapt to different layouts and scales. The piece is structured so it can be retuned to venues ranging from white-cube galleries to historic or industrial sites, keeping the core logic while letting each space shape the outcome.

In parallel, I’m building a series of small light-and-sound objects—tangible pieces that embed video or motion imagery into compact sculptures. The goal is to balance digital systems with material presence: wood, metal, glass, and translucent surfaces that carry light and vibration. These works translate my generative approach into intimate forms you can live with, not just visit.

I’m also opening the practice to new collaborations—especially with architects, fabricators, and musicians—to test alternative spatial experiences in public and unconventional contexts. Across all of this, the throughline remains the same: refining “reflection machines” that let audiences find themselves in the work, whether at room scale or object scale.